In the prevailing preference for a male child, this doctor witnesses a sluggish change

BILKULONLINE

SUNDAY Special

New Delhi, Sep 22: It begins with the pang of a score of bones snapping all at once, the process is intense for both delivering a baby—the mother and the obstetrician—each time.

While the state of the mother is a curious mix of expectation and anticipation about the health of her newborn, through feelings of uncertainty, pain, exhaustion, and sometimes guilt owing to societal pressures, her doctor seldom remains unaffected by the swirl of her emotional roller coaster.

Childbirth is a transformative experience—a journey through shaping one’s identity all over again, and the resilience of a woman. Yet this rollercoaster of emotional crests and troughs could come to a screeching halt at a crucial turn—and is often damaging—when a woman bears a child that is not a boy.

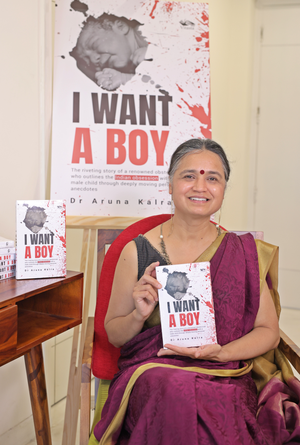

Gynaecologist and author Dr Aruna Kalra, with her autobiographical account ‘I Want a Boy’ (Vitasta), peppered with personal anecdotes, brings to highlight the reality of preference for a male child, and consequently, the persistent evil practice of female foeticide, oppression of women, and atrocities on them. It is estimated that 4-12 million female foetuses have been aborted over the last three decades. And the figures continue to increase.

As an obstetrician, Dr Kalra said. “Witnessing childbirth involves navigating a rollercoaster of emotions. There’s the physical challenge of managing the delivery at odd hours and ensuring the safety of both mother and child. Emotionally, there’s empathy for the woman’s experience and the weight of the responsibility to support and guide her.” “Psychologically, it’s about balancing professional detachment with personal empathy, managing stress, and finding fulfilment in facilitating such a significant life event and post-delivery psychological support,” she added. How different is giving birth to a boy in contrast with bearing a girl? From a medical standpoint, the physical process of birthing a child is the same irrespective of the baby’s gender.

However, societal attitudes can influence the emotional experience, said Dr Kalra. “In our orthodox society, having a boy is celebrated more, reflecting a preference for sons due to traditional beliefs about lineage and inheritance. This preference is equally present in every socio-economic and cultural group,” she explained. Interestingly, in wealthier classes with more progressive outlooks and education, “traditional gender biases are more deeply entrenched,” revealed Dr Kalra.

Some opt for medical interventions such as sex-selective practices to increase the likelihood of having a boy, often due to cultural or familial pressures. This can involve techniques like pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) or even illegal practices like sex-selective abortions. “Despite legal restrictions, these practices persist, driven by deeply rooted gender preferences,” said the gynaecologist. In the persisting malpractice of gender selection and perceptions about family, the author believes that education is pivotal in addressing and correcting this cultural norm. The author maintains that public awareness campaigns can challenge gender stereotypes and emphasise the value of all children equally. Integrating gender sensitisation and equality education into school curricula, promoting positive stories of women and girls, and creating supportive community programmes could be helpful too. “Legal enforcement against illegal sex-selective practices must be paired with societal efforts to shift cultural attitudes towards gender,” she said. How does a perfect world look to Dr Kalra if people were not selective and biased about the children they chose to raise? “In a perfect world, every child would be valued equally, regardless of gender.

Families would be supported in nurturing their children based on their individual needs and potential, rather than societal pressures,” she said. In her personal experience, navigating the expectations of being a “perfect mother” while balancing career and personal aspirations was nothing short of challenging, “yet it also reinforced my commitment to advocating for a more equitable view of motherhood.” The medic and observer is, however, happy to witness a favourable change in younger couples who “see children as children and wish for a good healthy child, daughter or son.”